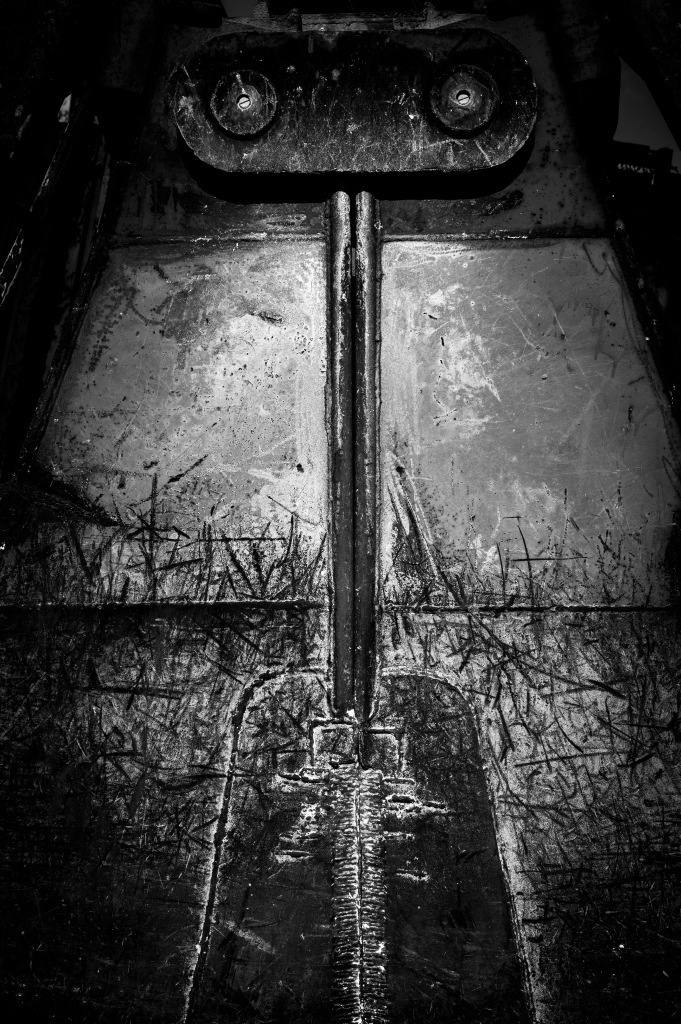

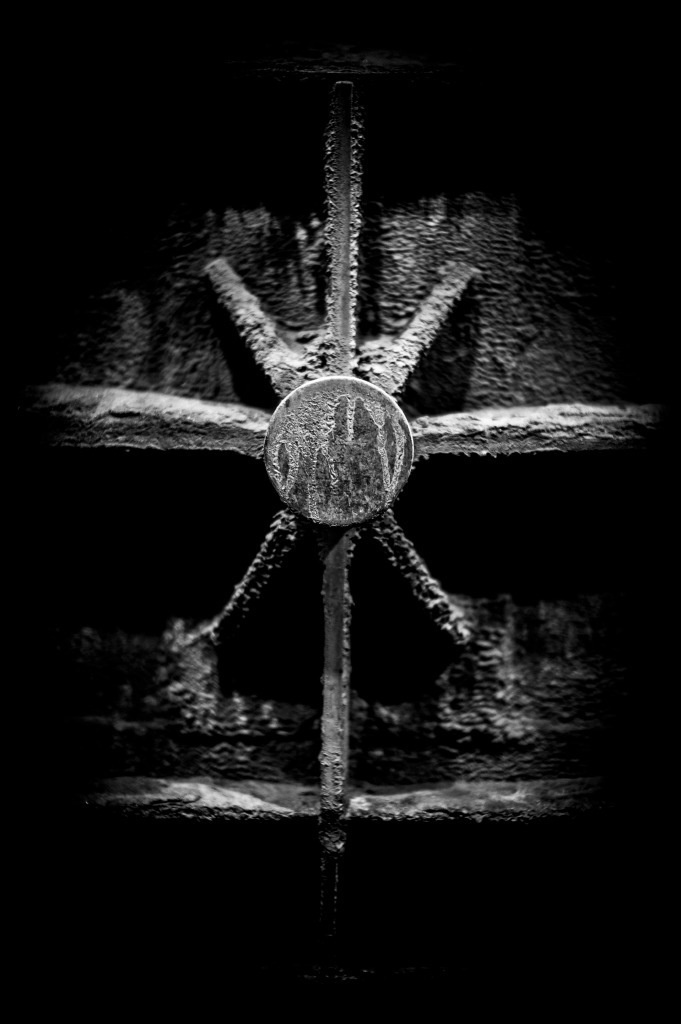

NORILSK

In a memorable image from Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte (1961), Lidia stands at the corner of a building, framed by the developing outskirts of Milan during the miracolo economico. As seemingly stagnant contemporary ‘ruins’ decay around her, they simultaneously continue to expand with Milan’s economic development. This collapse of history into place is captured in the photographs by Grigoriy Yaroshenko contained in this book. The pictures take the Russian city of Norilsk as their protagonist—somewhat analogous to Antonioni’s portrayal of Lidia. The city’s collective memory includes traumas that are inscribed into its ruins: composed of massive and expansive housing blocks, seemingly infinite mines, quarries, and factories, and a permafrost extending towards the horizon in every direction. Its operating factories and plants are as much a fabric of the city as its natural geography. It was founded as a site for forced labour, constituting the centre of the Norillag system of GULAG labour camps, with 72,500 inmates at its peak in 1951. Looking to Yaroshenko’s series of pictures, it is clear that the past and present can not be separated from one another — the former informs the latter, and the latter contains the former’s mark, rhythm, and material/immaterial ruins. Yaroshenko’s wandering eye has captured how a city can emerge from darkness in more ways than one, and can carve out a present without forsaking its history in the process.

Essay: Andreas Petrossiants