When I was 12 my father bought a house in a village. 34 years later when the house became old and run down, he decided to build a new one right in the backyard. For six years he would spend all his earnings on this project. One summer my wife and sons agreed to spend the holidays there in order to relax, go mushroom picking and fishing; and of course, do something useful for the construction. My acquaintance Boris offered to help: he said he knew five Uzbeks who can dig a trench better than a bulldozer and there is no need for us to look for any other workers to do the summer plumbing. He suggested it was best to dig the two-meter trench, lay the pipes, and forget about it until the rainy weather comes.

The next morning I woke up to the sound of the approaching tractor. Three Uzbeks arrived. Holick was the oldest one of some 40+ years old, and two younger ones, Obid and Navruz. They didn’t understand much Russian, just nodded their heads and said “ok” and “understand”. They started to dig. The trench was growing bigger and bigger, but there was no rain. They buried nine plumbing rings in different places inside the 55-meter trench.

Once the trench was ready I got inside it and started to take photos. I didn’t know what and why I was filming, I just took pictures of “my” Uzbeks. They were dirty and tired, digging meter by meter, never complaining, never asking for anything, from eight till eight with a short lunch break. My wife made them pasta with cheap tinned meat. Boris asked us not to feed them too well not to spoil them.

It also appeared to me he was physically hitting them, not because he was angry, but because it was customary to do so that they stayed scared of him. He said that these “animals” cannot be treated in any other way. He took away their passports and said they could not disappear that way, he said it was better. I knew Boris for 20 years and I never question his words; I tried not to give it too much thought. Why should I… it’s not my problem, I presumed.

This continued for almost the whole month. Apart from digging the trench they removed all the rubbish, built a fence, brought all sand and soil to the construction site, and leveled it. Now we can play football there if we put down some grass.

Our holiday came to an end, but I could not stop. I filmed them every day, a little at first, and then — more and more. They stopped paying attention to my filming them. At first, they smiled and made silly faces, but later got used to it. They didn’t even ask me why I filmed them; perhaps they could not or were afraid to ask. At some point, I experienced a strange and unpleasant feeling of having total power over them.

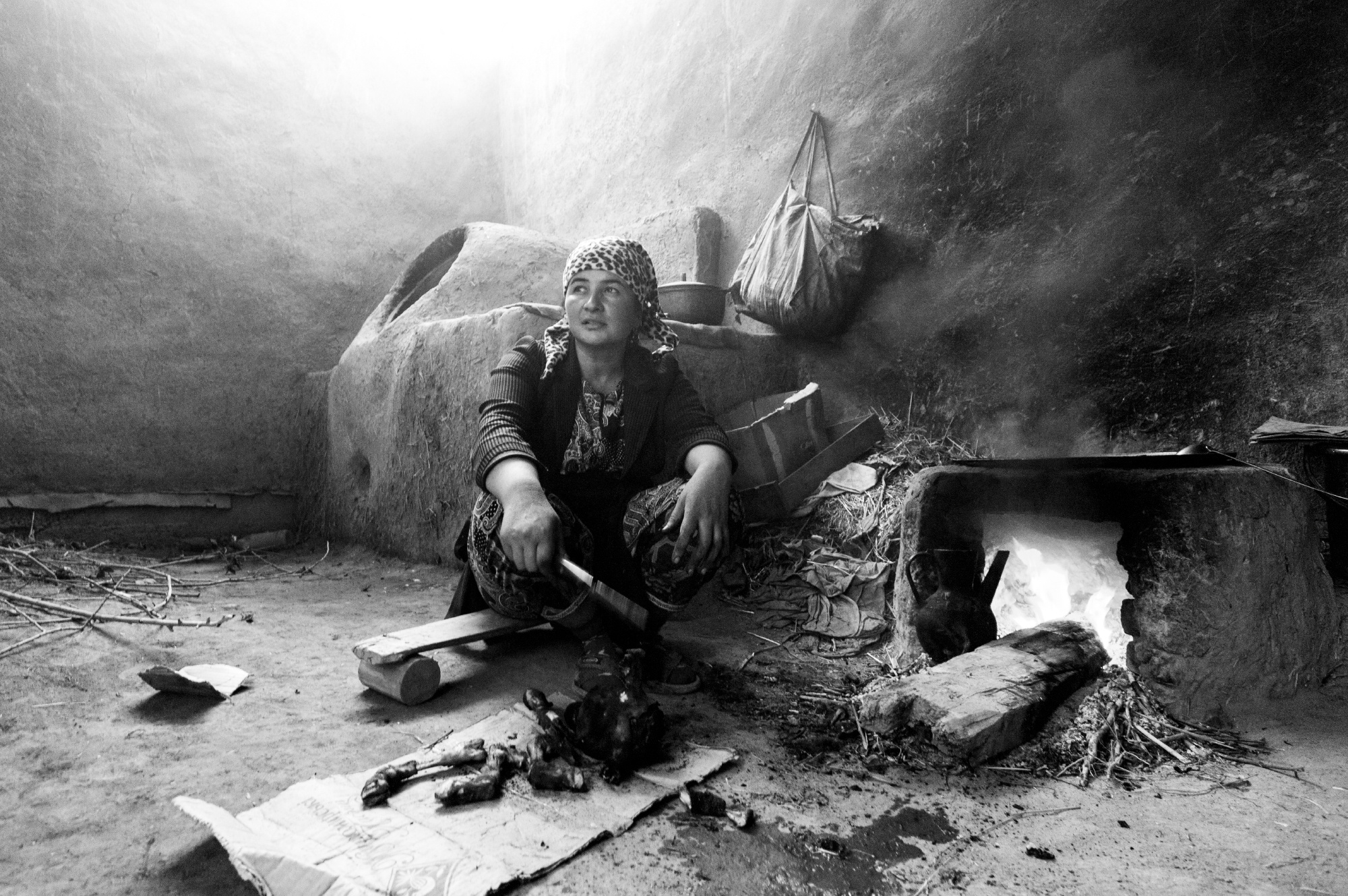

One day I went to visit the place where they lived. It was a small dirty house near a road, which looked more like a barrack, almost without windows, dark and murky like their life. Outside the house, there was a tractor and a bull. They were eating poorly, but better than I was feeding them. On Saturday when the trench was almost covered up they invited me to eat a pilaf with them.

There were two more people; all five were relatives from the same village near Bukhara. Mubin was a pilaf cook. I was treated like a tsar, given the best spoon and plate and the largest portion of meat. It was tasty, but I didn’t finish the whole portion, I took the rest with me saying that I would like my parents to try it. I asked them when they are going back to Uzbekistan and how they are going to get there. Not that I cared, it was asked simply out of curiosity. Nusrat, who worked in Moscow for three years, said that they usually took a taxi, which cost 7,500 rubles per person for 3,500 kilometers. He said they had to travel for 3 days sleeping in the car or at some cheap place at 50-100 rubles per night per person. They asked if I wanted to go with them. I refused politely, bought beers for everyone, and went home.

Eventually, we became friends. I could not sleep at night thinking about them. What poverty and desperation pushed people to such hard travels, 5 months without the family, without women and weekends, all for 500 dollars salary a month? Who are they, how they live, and why the hate for these poor people became normal? Why are we chasing them away, mocking them, and arrogantly turning away from them, refusing to shake hands? Why do we change their names into Russian names (Holick — Kolya, Mubeck — Misha, Obid — Oleg). Are we unable to remember their real names? They are wonderful, hardworking people, and maybe, because of them we feel so much better and successful ourselves. We are unwilling to do the jobs they are always ready to take. Forgive us, my dear friends from Uzbekistan, Tadzhikistan, Kirgizstan, and many others unknown to us places. I hope your life will become better; your children have someone to be proud of …

I

asked my mother to make better food for them. I said that I will take them home

myself. I hope to come back again

or meet them there and we will surely continue our story.

2013